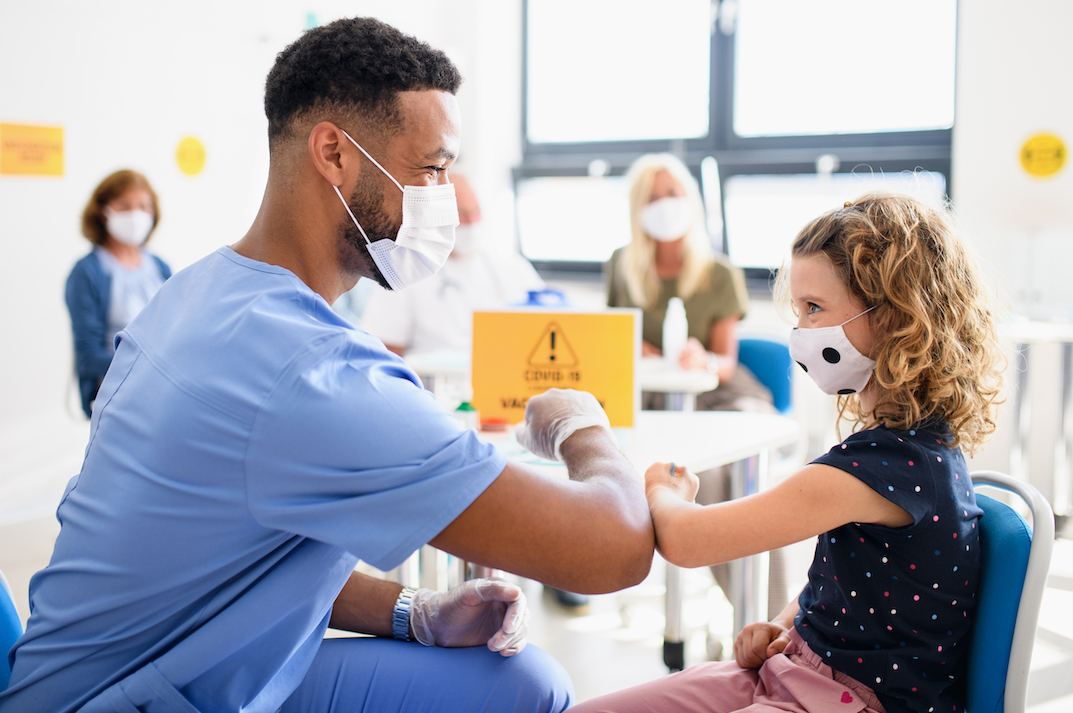

In the press: Vaccinating children for Coronavirus; a Family Law perspective

04 Oct, 2021 - Divorce and Family | by Grosvenor LawThe chief medical officers for England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have now recommended that all children aged 12 to 15 years be vaccinated for Coronavirus. The rationale is currently said to be that it is to reduce disruption to their education. Professor Chris Whitty, the Chief Medical Officer for England, one of the most respected of experts presented to the British public during the pandemic admitted it was a difficult decision, which to some people suggests that there might be an element of doubt about whether this is the right decision or not.

The uncertainty and nuance surrounding this decision is likely to be fertile ground for disagreement not just between parents, but between one or both parents and a child.

Most parents have parental responsibility for a child, which means they can make decisions relating to the child’s upbringing and general welfare. It usually concerns decisions about the school the child attends, the religion they follow and, of course, consent to medical treatment. If there is a dispute about an issue between parents, one or other of them can refer the matter to the court for a judge to decide.

On 1 October 2021 the High Court rejected a mother’s bid to suspend the children’s Coronavirus vaccine programme, offered to children aged 12 to 17 years old, including her two children. Her claim against the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) was for an injunction and judicial review of the decision of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to licence the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines for children. At a later date Mr Justice Jay will consider her claim that the government was wrong to set up the programme. The mother’s case is that the virus poses an exceptionally low risk to otherwise healthy children and that the vaccination of such children is unnecessary.

The DHSC said that the MHRA, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) and the chief medical officers have assessed the data and reached a balanced view, and although the mother takes a different view, that does not make the original assessment by the experts unlawful. On behalf of the DHSC it was said that the vaccination programme is entirely voluntary and there is no question of mandatory vaccination of children.

While the uptake of vaccines for children is expected to be lower than the older population one might question for how long the DHSC will maintain the stance that the programme is “entirely voluntary”. In 2020 the court of appeal allowed a local authority to vaccinate a healthy child in care, notwithstanding that both parents disagreed. While this was a public law case it was said that it would be difficult to foresee a case in which a vaccination approved for use in children would not be assumed to be in the child’s best interests.

Later in 2020 a father applied to the court for an order that his children should be vaccinated for the usual childhood immunisations, including for Covid-19. The mother’s objections included an array of medical research and evidence, including the submission that vaccination does not prevent the child catching the disease. Although the judge was clear that his decision did not extend to any Covid-19 vaccination, it by that stage not having been approved, he did say that “it is very difficult to foresee a situation in which a vaccination against Covid-19 approved for use in children would not be endorsed… as being in a child’s best interests…”

In 2014 the court was clear that parental responsibility is to exercised for the benefit of the child, not for the parent, and it then follows not for anyone else.

Further difficulties ensue if the child has a different view to the parents. A child is defined a someone under 18 years old. While various pieces of legislation allow one aged 16 or over to make their own decisions about various issues, a child under 16 might also be able to consent, and conversely refuse treatment if they have “Gillick competence”. This recognises that a child’s ability to make important decisions about their life increases as they get older.

A medical professional who administers Covid-19 vaccine to a child without the consent of a parent, or a capable child or court order could be guilty of a criminal offence. Schools and medics should proceed with caution unless both parents and the child agree to be vaccinated.

The Covid-19 vaccination programme for children could cause multiple legal problems for families and schools, including clashes between parents who disagree whether their child should be vaccinated against Coronavirus, school versus parents, and children facing peer pressure.

Jacqueline Fitzgerald is a partner at Grosvenor Law and deals with all aspects of family law

A version of this blog was cited in the following article https://sustainhealth.fit/lifestyle/jabs-for-children-legality/

The contents of our blog posts do not constitute legal advice and are provided for general information purposes only.